What is Nystagmus?

Nystagmus is a visual condition marked by involuntary, rhythmic eye movements, often described as « jumping » or « dancing » motions. These movements can affect both eyes or just one, though it’s more frequent they affect both.

The involuntary eye movements may appear as either rapid or slow motions, exhibiting various patterns such as circular, vertical, or horizontal motions. As a result, individuals with nystagmus may struggle to maintain steady focus on objects, leading to reduced visual acuity. For example, if persistent into adulthood, in individuals with Blue Cone Monochromacy, it can lead to challenges with reading. Additionally, these movements can also impact balance and coordination. In the case of Blue cone Monochromacy, nystagmus becomes worse in moments of stress or fatigue as reported by many members of our community.

Nystagmus is typically classified as congenital or acquired, with multiple subcategories.

Congenital nystagmus, sometimes also referred to as « Early-Onset Nystagmus » or « Infantile Nystagmus, » appears at birth or emerges within the initial months of life. Typically, infants begin exhibiting symptoms between six weeks and three months old, primarily experiencing blurry vision. If the onset occurs after six months of age, it is categorized as acquired nystagmus. Congenital nystagmus can be idiopathic, meaning it can occur without any other underlying medical condition, but it may also be linked to various ocular or neurological conditions.

Acquired nystagmus emerges later, starting as early as six months of age but potentially occurring at any time afterward, with a higher incidence observed in adults. It can have many etiologies and it also may be linked to medical conditions warranting further evaluation by medical professionals.

Muscles and Cranial Nerves involved in Nystagmus and Strabismus

Muscles – There are six muscles that enable eye movement

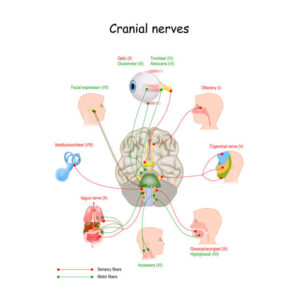

Nerves -There are three pairs of cranial nerves that control muscles of eye movement (each eye is controlled by one nerve of each pair). Damage to these nerves can interfere with eye muscles, causing nystagmus. The rest of the nerves in your body emerge from the spinal cord but all the cranial nerves, including the trochlear nerve, come from your brain.

- The oculomotor nerve (cranial nerve three, CNIII) controls several muscles that move your eyes: the superior rectus muscle, the medial rectus muscle, the inferior rectus muscle, and the inferior oblique muscle. These muscles move your eyes straight up and down and toward your nose. There are 12 sets of cranial nerves CN. The oculomotor nerve is the third cranial nerve (CN III). It allows movement of the eye muscles, constriction of the pupil, focusing the eyes and the position of the upper eyelid.

- The trochlear nerve (cranial nerve four, CNIV) controls the superior oblique muscle that moves your eye in a direction that is down and away from your nose.

- The abducens nerve (cranial nerve six, CNVI) controls the lateral rectus muscle, which moves your eye outward and away from your nose.

- The vestibulocochlear nerve (cranial nerve eight) mediates your sense of sound and balance. It does not control eye movement, but a deficit in this nerve can impair balance to a degree that causes nystagmus.

Rarely, surgery is performed to change the position of the muscles that move the eyes. While this surgery does not cure nystagmus, it may reduce how much a person needs to turn his or her head for better vision.

Nystagmus becomes worse in moments of stress or fatigue as reported by many members of our community. The exact cause is often unknown.

Nystagmus, Strabismus and Blue Cone Monochromacy

Some individuals affected by Blue Cone Monochromacy report strabismus, some other report nystagmus in adult life. The first symptom observed in all newborn with Blue Cone Monochromacy is congenital nystagmus in 2-3 months old newborns. Nystagmus decreases with age and only a fraction of patients reports it in adulthood.

https://www.blueconemonochromacy.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/RPReplay_Final17065366523.mp4?_=1

Video of a 4-months baby with Blue Cone Monochromacy showing Nystagmus

Video of an adult affected by BCM with Nystagmus

Perceptions

Children affected by congenital nystagmus typically perceive the world similarly to other children, albeit with some degree of blurriness. Conversely, individuals with nystagmus that develops in adulthood often describe a sensation of movement or « shaking » in their visual field, known as oscillopsia.

Null Point

The intensity of the eye movements in nystagmus can vary depending on the direction of the individual’s gaze. Therefore, as reduced eye shaking implicates better vision, a way in which some of the children affected by nystagmus manage to optimize their vision is by adjusting their head to access their null point. This term refers to a specific head position where the involuntary eye movements are minimized, allowing for reduced oscillations of their eyes and improved visual acuity. While not all children with nystagmus have a null point, if they do, it’s important not to encourage them to turn their head in the opposite direction, as this could worsen their vision.

Causes

Nystagmus may be idiopathic (no known cause), be inherited or be associated with other medical conditions. A list of conditions possibly associated with nystagmus includes:

- Inherited conditions (such as Blue Cone Monochromacy, Achromatopsia and Leber Congenital Amaurosis)

- Albinism

- Congenital cataracts

- Inner ear disorders

- Neurological disorders

- Systemic disorders

- Visual problems

- Inflammatory diseases

- Medications and drugs use

- Trauma

- Stroke

- Brain tumor

Recognizing the underlying cause of nystagmus is crucial for effective management and treatment. As such, a comprehensive assessment by healthcare experts, such as ophthalmologists and neurologists, is often necessary to determine the specific cause and develop an appropriate management plan tailored to the individual’s needs.

External Resources

- American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus – https://aapos.org/glossary/nystagmus

- American Nystagmus Network – https://nystagmus.org/

- Cleveland Clinic – https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/22064-nystagmus

- Fighting Blindness – https://www.fightingblindness.ie/living-with-sight-loss/eye-conditions/nystagmus/

- Johns Hopkins Medicine – https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/nystagmus